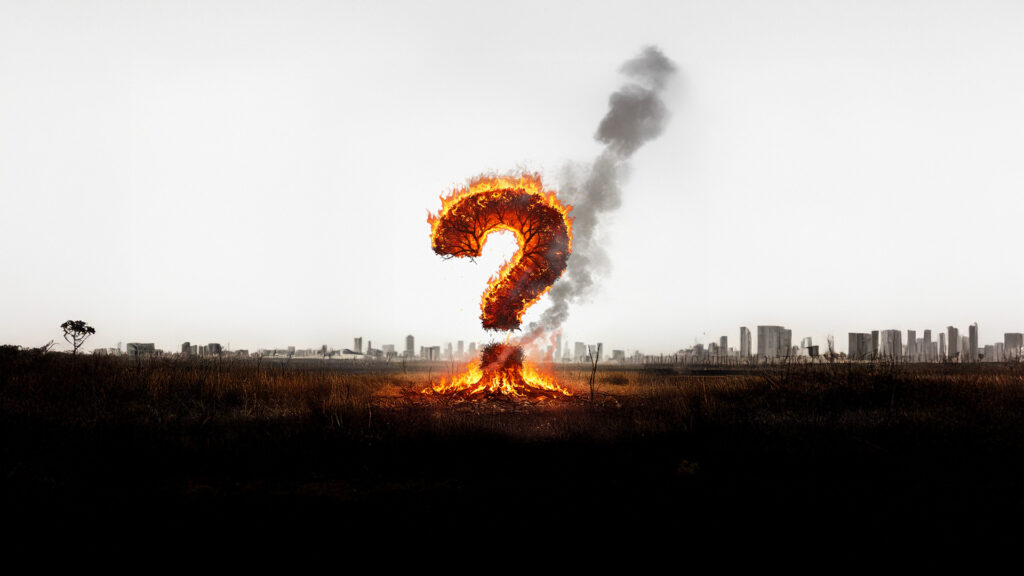

Hutchinson, Kansas, Norman, Oklahoma, Auburn, Alabama, Biloxi, Mississippi, Fort Smith, Arkansas, Sioux City, Iowa. All these places now face the rising threat of urban conflagrations. Traditionally seen as a Western state’s problem, wildfires are now affecting regions nationwide. Join Ryan and Doug in this episode as they discuss how recent devastating wildfires defy traditional classifications, forcing a reevaluation of urban planning and firefighting strategies. Learn about new risk factors, the pivotal role of building codes, and how communities can adapt to these evolving threats. If you’re a planner, homeowner, or simply concerned about fire safety, this conversation is essential.

Links:

- America’s urban wildfire crisis: More that 1,100 communities at risk

- ‘It Got Everything’: Oklahoma Residents Who Escaped Fires Brace for Losses

- Wildfire Risk to Communities

Timestamps:

00:00 Introduction: Unexpected Wildfire Risks

00:19 Historical Perspective on Wildfires

00:50 The Rise of Urban Conflagrations

01:46 Defining Urban Conflagrations

02:26 Case Studies and Personal Insights

03:04 Challenges in Fighting Urban Conflagrations

05:08 Differences Between Wildfires and Urban Conflagrations

08:06 Identifying At-Risk Communities

09:09 The Paradigm Shift in Urban Planning

12:05 Solutions and Mitigation Strategies

16:39 The Broader Implications

21:47 Conclusion and Call to Action

Episode hosts

Ryan Maye Handy

Ryan is a wildfire and land use expert for the Community Planning Assistance for Wildfire program. Her experience as an urban planner and former journalist brings invaluable insights to communities that must prepare for increasing wildfire risks.

Doug Green

Doug brings two decades of professional experience in fire departments and as a land use planner to the Community Assistance for Wildfire program. His practical insights and expertise in fire operations has supported dozens of communities working to reduce wildfire risks.

Transcript

Transcript edited for clarity

Ryan Handy: In the last six years, North American wildfires seem to have hit a new level of destruction. They’ve burned thousands of homes, leveled entire communities, and killed hundreds of people. We haven’t seen this kind of devastation since the great urban fires of the late 19th and early 20th centuries ravaged cities like Chicago and San Francisco.

And while we’ve called these recent events in Colorado, California, and Hawaii “wildfires,” they have burned homes and defied the systems we’ve put in place to stop them. When they’re burning, they seem unstoppable.

At Headwaters Economics, we’ve worked to pinpoint the communities at risk of these urban conflagrations. Surprisingly, many are not in typically wildfire-prone areas. These fires are actively changing urban planning and firefighting, and that’s what we want to explore today. I have several burning questions on this topic that I’ve been wanting to explore with Doug for a long time. For instance, are these conflagrations really wildfires? What makes them different? How do we stop them? And why does any of that matter for me as a planner or for you as a homeowner? Let’s get into it.

Doug, this is a topic I’ve been looking forward to picking your brain on for a while. I remember when the Marshall Fire happened in Colorado. It burned thousands of homes in a suburban neighborhood outside of Boulder, and it wasn’t near any dense forest. I remember thinking, “That’s not a wildfire.” When the fires in LA happened, you were the first person to agree with me. So if these massive urban fires aren’t wildfires, what are they? What causes them, and what stops them?

I think you’re the perfect person to answer this. You’re a wildfire expert, but you were also a structural firefighter in Oregon for 25 years, so you’re deeply familiar with what it takes to save a home from a fire.

Doug Green: Well, thanks, Ryan. It’s certainly not a simple question. Historically, as you said, we called them urban conflagrations. That was the term used for the great city fires in the late 1800s and early 1900s. As building codes and construction techniques improved, we stopped using that term for a long time. It only came back into use in the early 1990s when wildfires started entering our cities, particularly in Southern California.

There’s really nothing else to define them. We’ve talked about them as “urban wildfires,” but as you said, they’re not wildfires. So, “urban conflagration” has been used to define any large, uncontrollable fire that spreads rapidly through a densely populated area, causing widespread destruction. It’s a term that can be confusing to the public, but it accurately describes what we saw in Lahaina, Los Angeles, and with the Marshall Fire—fires burning into urban areas that aren’t traditional wildfires.

Ryan: You and I have been researching how catastrophic fires from more than a century ago influenced modern building codes. As I was writing about the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 or the 1906 San Francisco fire, I thought of them as things of the past. They happened when our cities were made of wood, before we had fire departments.

But I began to realize they are no longer things of the past. The Camp Fire in 2018 destroyed more than 14,000 homes. The Marshall Fire in 2021 destroyed over a thousand, and the LA fires this year destroyed more than 11,000 structures. These urban fires were a thing of the past. Why have they come back?

Doug: You’re right. Originally, we realized the way to stop cities from burning down was to use different building techniques, adopt codes, and require sprinkler systems. We stopped building wooden boardwalks. We developed a science that allowed us to stop those massive urban fires.

Now, we’re seeing them again, for different reasons but with similar outcomes. We have spent decades building in the wildland-urban interface with techniques that didn’t account for this kind of fire. Our codes were designed to handle a single structure fire, assuming we’d have plenty of resources to attack it. We never designed our streets or landscape codes to account for fires being driven into urban areas by hurricane-force winds that quickly overrun fire departments. That’s what we started seeing in the 1990s and what continues today. The solutions are the same: building differently and recognizing these for what they are. These are not wildfires; they are urban conflagrations, and they require different solutions.

Ryan: At Headwaters, we wanted to identify the specific causes. After the LA fires, we used wildfire risk maps we maintain with the U.S. Forest Service to predict other places where these might happen. Using examples from the past five years, we found these urban conflagrations share common characteristics: they’re fueled by hurricane-force winds, they’re in areas with high wildfire exposure, and they occur where there’s a certain density of homes and structures.

Our analysis identified more than a thousand at-risk communities across the country. And these fires feel different from what we’ve seen before, even from the 1990s. They are different in how and what they burn, how we fight them, and the consequences they leave behind.

Doug: You’re exactly right. Let’s break that down.

First, they’re different in where they burn. These fires often ignite within or adjacent to urban areas, not in forests or large tracts of public land. The ignition source isn’t lightning. They burn in places we haven’t normally seen fires like this.

Second, the pattern of spread has caught everyone off guard. Fueled by hurricane-force winds, the embers travel far and fast, quickly overrunning the fire departments that are simultaneously trying to evacuate people.

Third, and this is one of the biggest differences, is the primary fuel source. In a wildfire, the fuel is trees and vegetation. We understand how to fight that. We contain it, we flank it. In an urban conflagration, the primary fuel is man-made combustible material: homes, sheds, fences, cars, boats, RVs. Not only do these materials burn incredibly hot, but they also produce enormous, dinner-plate-sized embers that are blown downwind, starting more fires and accelerating the spread.

Ryan: I want to dive into your background as a structural firefighter. How do you typically manage a single house fire, and why is that impossible during an urban conflagration?

Doug: With a single structure fire, departments know how to attack it. We have the resources, and modern building codes help keep the fire in check. If wind is a concern, we have the resources to prevent it from spreading to adjacent homes. We’re dealing with a single point of ignition.

In an urban conflagration, you have thousands of large embers landing on fences, in bushes, on roofs, and in gutters. Suddenly, you have dozens or more homes catching fire at once. No structural fire department can fight that. You’re asking them to fight a wildland-scale fire within an urban area, and that’s not possible. Their primary goal shifts to evacuation because the fire is moving too fast and they don’t have the resources to fight dozens of structure fires at once.

Ryan: This gets at a fundamental tension in the fire service: the difference between wildland firefighting and structural firefighting. In wildland training, I learned that the decisions are about triage. You can’t always save every home, and firefighters often have to walk away from a structure because it’s not safe to defend. That’s why we encourage people to create defensible space—their home often has to stand on its own.

So, in an urban conflagration, you’re fighting something with the power of a wildfire, but in an area with more fuel, fewer escape routes, and a lot more people who need to get out.

Doug: Exactly. In a wildland fire, you’re protecting resources and there’s usually plenty of time to evacuate people. In an urban conflagration, the priority is saving lives. When that becomes the priority, the tactics change dramatically. Traditional methods for fighting either structure fires or wildfires don’t apply. It’s a combination of both, which is why defining it correctly is so important for developing risk factors and mitigation strategies.

Ryan: This gets back to the existential question: why is it so important to define these fires correctly? As planners and wildfire experts, we address wildfire risk, but now we’re working with communities facing urban conflagrations. How does this change things for us?

Doug: If we view these only as wildfires, our mitigation efforts will be based on the wrong risk factors—things like drought and vegetation type. While those can be influences, they aren’t the root cause.

Urban conflagration risk factors are about the built environment: building materials, density, and infrastructure. It’s a paradigm shift. We have to think about how to stop fire from transferring from one structure to another in an urban area. This is a relatively new science. How do we build structures that won’t burn when the one next door is on fire? How do we do that cost-effectively in high-density areas while still allowing people to have the aesthetics they want, like vegetation and fences? Planners are starting to tackle these questions with help from fire departments.

Ryan: That paradigm shift is critical. We were recently reviewing a community’s wildfire protection plan, and every single action item was about fuels mitigation—thinning trees and clearing vegetation. There was virtually no mention of the built environment: landscaping codes, building construction, and how homes themselves contribute to fire risk. It shows that many communities have yet to make the shift to understanding that this is no longer just about vegetation. Neighborhoods are burning each other down.

And that explains why, in photos from these events, you see the homes are gone but the trees are still standing, or the lawn is still green.

Ryan: So, to stop these urban conflagrations, the answer is the same as it was a century ago: we have to think about building differently. To summarize a few key points:

- Homes catch each other on fire. It’s not enough for one or two homes to address their risk; the whole neighborhood needs to buy in.

- Your home’s best chance of survival is the chance you give it. It may not be safe for firefighters to reach you.

- Building to fire-resistant standards is not substantially more expensive than traditional methods.

Doug: This is one of the most frustrating parts for us, because we know the science. We solved this problem a hundred years ago. We know how to keep these communities from burning. It comes down to two things: social science—educating people that this is a different kind of problem—and leadership. We need decision-makers with the fortitude to make the tough choices about how we build. We’ve mapped the at-risk communities. We have the solutions. We just need to take the tough step of implementing them.

Ryan: What’s challenging is that our research shows the burden of change applies in many more places than we originally thought—communities that may have never considered wildfire a major hazard.

For example, around St. Patrick’s Day, a wildfire in Stillwater, Oklahoma, destroyed hundreds of homes, the most in state history. I was reading about it in The New York Times, and one paragraph was a striking summary of what’s happening. It said: “The fires in Oklahoma were fueled by low humidity, dry vegetation, and hurricane-force winds, creating dystopian landscapes of orange skies, downed utility lines, and homes reduced to piles of sticks. An eerie echo of scenes from Los Angeles just two months before.”

Stillwater has high fire danger according to the maps, but the community isn’t used to dealing with it on this scale of urban destruction.

Doug: The fires in Oklahoma highlight that this is not just a problem for the Western states. We know there’s huge fire risk in the South—New Jersey, Florida, the Carolinas have all had large fires. In many of these places, the hazard-planning priorities are hurricanes, tornadoes, or winter storms. This is a more challenging problem for them.

Ryan: This brings us back to the existential part of this discussion. I looked at our map of urban conflagration risk and found places I never would have associated with this threat: Hutchinson, Kansas; Norman, Oklahoma; Auburn, Alabama; Biloxi, Mississippi; Fort Smith, Arkansas; Sioux City, Iowa. When I think of Biloxi, I think about hurricanes and flooding. Suddenly, all of these places need to be worried about urban conflagrations.

Doug: That list caught me off guard as well. I’ve worked on fire issues in the South and East for years, but Biloxi, Mississippi, was never at the top of my list for high wildfire potential. It just shows that when the right conditions align—wind, low humidity, vulnerable homes—this can be a real problem anywhere.

Ryan: I think that’s a good place to end it today. We will link in the show notes to our latest research identifying the thousand-plus communities at risk of urban conflagrations. Please take a look and see if your community is on the list. If you have questions, please reach out.

Thanks again, Doug.

Doug: Thanks, Ryan.

Ryan: Join us for our next episode, when we will be discussing how to rebuild after a wildfire. Thanks for joining us.